Chichilaki

Embracing syncretism + letting it all burn.

This year has begun as a complete clusterfuck. Illness, pet emergencies, eclipsed writing deadlines, and work projects rolling rudely over from last year into the present. I’m in need of some deep chthonic rituals; ideally the kind that involve libations and setting things on fire.

In Georgian Orthodox tradition, today is Natlisgheba (ნათლისღება) or the "Epiphany” which commemorates the baptism of Jesus in the Jordan River and his divine manifestation to the world as the Son of God. It is one of the country’s major feast days, and officially marks the end of the winter festive season in Georgia and the beginning of the new year.

Keeping on theme, the day’s central liturgical rite is the Great Blessing of Waters. Priests bless rivers, lakes, or simply vessels of water, which believers take home, considering it to have special spiritual and medicinal properties throughout the year. In colder regions, people even submerge themselves in icy waters three times to invoke the Holy Trinity as an act of devotion; a way to purify the soul and renew one’s faith.

The other uniquely Georgian ritual which takes place on the Epiphany is the burning of “chichilaki” to ritually cleanse the previous year’s troubles and usher in good fortune with the new.

Chichilaki are rather whimsical wooden ornaments carved from dried hazelnut or walnut branches, which are shaved to make curly fronds in the shape of a fir tree. The masters who traditionally create these pieces are referred to as Veluri (ველური, meaning “wild”), as they venture deep into the forest in December to forage for the branches, before soaking and heating them over a fire to create the curls.

Creating and burning chichilaki is an old folk practice rooted in ancient cosmology, deriving from the Black Sea regions of Guria and Samegrelo, in what was originally the Kingdom of Colchis. The trees are decorated with fruits, especially pomegranates, hawthorn berries and apples, along with the leaves of evergreen plants and a piece of ceremonial bread (bokeli) on top as offerings for a fecund harvest. With their celestial markers and fiery sacraments, Chichilaki honour the sun as a life-force and herald its light and warmth after the long days of winter.

After Georgia was Christianised in the fourth century AD, the chichilaki’s folk origins assumed theological dimensions and became associated with St. Basil (thought to resemble his curly beard) and Christmas. Under Soviet rule chichilaki were outlawed along with all other religious customs, and holy winter celebrations were transposed onto the suitably profane date of New Year’s Eve on the 31st December.

What occurred in reality, however, is what has always happened in Georgia: religio-cultural traditions simply adopted secular dressings and survived by taking on new forms.

In recent years, as part of a broader movement in which Georgians are revitalizing their ancient heritage in the modern era, chichilaki have migrated into the heart of Georgian culture. They are now sold in the nation’s capital throughout the winter festive season, where they feature prominently in people’s homes and other public spaces. This year we have a beautiful large chichilaki in our cinema, which we bought from the local flower market one chilly morning while walking our dogs.

The Georgian winter holidays last several weeks and are woven from overlapping threads. Akhali Tseli (ახალი წელი) or New Year is celebrated on December 31st/January 1st with fireworks, gift-giving and feasts; Shoba (შობა) or Christmas is on January 7th, marked by midnight mass, candle-lighting, and the Alilo folk caroling procession; Dzveli Akhali Tseli (ძველით ახალი წელი) or “Old New Year” on January 14th, which calls for more gathering and feasting; and finally the Epiphany today, which blazons the new year.

This period is important to Georgians because the Georgian Orthodox church has served as the guardian of national identity through centuries of invasion and imperialism, safeguarding not only religious treasures but intellectual, linguistic and cultural traditions such as Georgia’s ancient qvevri winemaking and polyphonic singing. Throughout these festivities, chichilakis play a multivalent role in connecting Georgia’s Orthodox faith with much older folk rituals associated with the winter solstice and the seasonal wheel of the year, as well as connection to community. They symbolize both the continuity of Georgian culture as well as its unique synthesis with other traditions.

Syncretism is everywhere in Georgia, especially in remote mountainous regions where Christianization occurred late and other invading forces penetrated unevenly, resulting in the mixing of pagan folklore with the worship of Christian deities. Syncretic practice is not merely a curiosity of the past, but the very architecture of Georgian identity and the reason it has survived through centuries of occupation and conquest.

Although Georgia is one of the oldest Christian countries in the world – preceded only by Armenia and Aksum (Ethiopia/Eritrea) – both Jews and Zoroastrians had a presence here first, preparing a fertile landscape of religious pluralism into which Christianity, brought by a young female missionary in 320 AD, could take root.

Jewish communities in Georgia date back to exiles from Nebuchadnezzar‘s destruction of the First Temple (around 586 BCE). They evolved into a unique group – one of the oldest Jewish diasporic communities in the world – ethnically known as ‘Georgian Jews’. They integrated local customs but maintained Jewish identity, and in the process contributed significantly to Georgian life. While other Jewish groups such as Mountain (Persian) Jews, Sephardim and Ashkenazim arrived later, bringing their own traditions and languages, Georgian Jews are credited with safeguarding Christianity when it was brought to the early developing nation. To this day, Georgian Kings and Queens are considered descendants of the Jewish King David - a belief institutionalized by the Georgian Orthodox Church – and it was a long-held tenet that unless members of the congregation lived alongside the Jewish community, they would not find prosperity or God’s protection.

At a folk level, Jewish Georgian fairytales are a unique blend of Jewish oral traditions, Talmudic parables, and Caucasian folklore, often documented in the Judeo-Georgian language (Kivruli). These stories reflect a history of over two millennia in Georgia, merging local myths with Jewish cultural and religious themes. Other practices such as the creation of magical amulets reveal a blend of Jewish mysticism with local Georgian folk belief.

However it is arguably Zoroastrianism, the ancient Persian fire religion, which has a more penetrating influence over Georgian religio-cultural heritage – even shaping the very structure of Georgia’s pre-Christian pantheon. The Georgian folk deity Armazi reflects this layering: scholars suggest the the name derives from the Zoroastrian god Ahura Mazda, or an indigenous Georgian moon cult that absorbed both Iranian and Anatolian Hittite elements. According to the medieval Georgian chronicle Kartlis tskhovreba, the first Georgian King Pharnavaz—himself bearing a Persian name and reputedly born of a Persian mother—erected a Zoroastrian-style fire altar with a towering golden idol of Armazi in the kingdom’s ancient capital, Mtskheta, in the third century BC.

Other epic tales from Iranian mythological tradition wove themselves into Georgian folklore, and Persian literary influence persisted through Georgia’s Golden Age to shape Shota Rustaveli’s national epic The Knight in the Panther’s Skin—a distinctly Georgian story in content in values, which drew its poetic structure from Persian epic traditions.

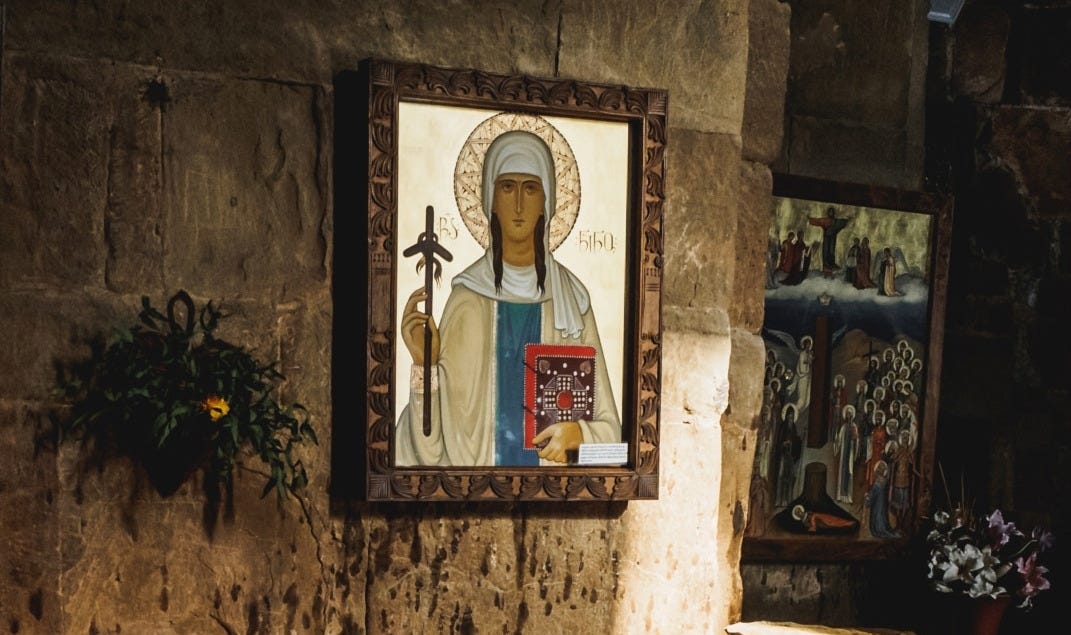

By the time Christianity arrived in the fourth century, Georgian cosmology already bore the richness of centuries of exchange: local astral and ancestor cults overlaid with Zoroastrian fire worship, Hellenistic gods and heroes, and a constellation of nature spirits tied to the Caucasian peaks and valleys. When St. Nino of Cappadocia brought the faith to Iberia, the cross she carried was made of grapevines, bound with strands of her own hair. Foreign missionary and Georgian botanika were woven together, to become the country’s most sacred symbol.

Syncretism is indeed the pattern in these lands; not the aberration. But at the crossroads of faiths and empires, cultural exchange surely moves in all directions.

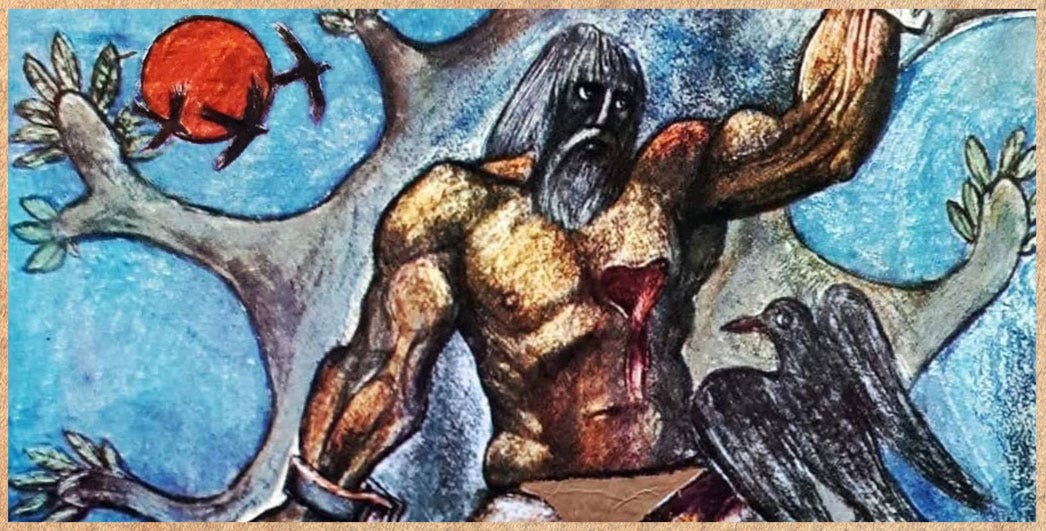

There are few myths more tragic than that of Prometheus, who stole fire from the gods to improve the lives of mortals, which invoked the wrath of Zeus. As punishment the titan was chained to a mountain in the Caucasus, condemned to endless suffering by an eagle devouring his liver each day, as the organ regenerated by night.

Yet Georgian oral tradition preserves a strikingly similar hero: Amirani, who angered the god Ghmerti by sharing his metalworking secrets with humans and – you guessed it - was chained high in the Caucasian slopes in damnation, subject to the same breed of liver-eating eagle. (A key difference, and what makes this story very Georgian, is that Amirani was chained with his loyal dog). Scholars trace Amirani’s legend to the third millennium BCE, potentially predating the Greek Prometheus by over a thousand years. Whatever the connections are between these two legends, it’s clear that Georgia wasn’t a passive vessel for external influence but also seeded myths that traveled outwards, into other worlds.

As I reflect on these patterns late into the night, they remind me that there’s more than one way to tell a story, create ritual, connect to place, or mark the passage of time.

In the spirit of conjuring epiphanies, both holy and profane, today I collected a small jar of water from the Leghvtakhevi Gorge which flows down from the mountains past the sulphur baths next to our apartment and out into the nearby Mtkvari river. This water, which contains the same sulfurous minerals that gave Tbilisi its name, now sits on a makeshift altar alongside some herbed salt from Svaneti, beeswax candles from the local Orthodox church, an icon of St Nino, a piece of shale from the ruins of an ancient watchtower near Kazbegi, and various seedpods I’ve pocketed absent-mindlessly on dog walks over the last few weeks. Smoke from burning frankincense resin wafts over me and mixes with the myrrh oil that I found hidden behind some books on my desk, now warmed by the pulse-points on my wrists.

Let it all burn, I say; it’s time to make way for the new.

Oh Danica - this was a wonderful history lesson to read this afternoon, thank you. It was such a fascinating cultural experience to share - far removed from the shark attack news back home. Thank you for helping us get to know the Georgian way of life and true spirit. Go burn!!! xxx

Thank you for this syncretic despatch Danica. Having just this morning been brushing up on the Christological debates and the early Coptic Christians, it was very nice to find your article and learn some new dimensions of faith, adaptation and survival.

You're certainly showing that "there’s more than one way to tell a story, create ritual, connect to place, or mark the passage of time."